MODULE 2: Setting the Stage: What Does Homeownership Mean to You?

ENHANCING AND IMPLEMENTING HOMEOWNERSHIP PROGRAMS IN NATIVE COMMUNITIES

Setting the Stage: What Does Homeownership Mean to You?

Setting the Stage: What Does Homeownership Mean to You?

In this course, we’ll be focusing on how to bring homeownership opportunities to your tribal nation and your community. We recognize that homeownership may not be on everyone’s radar, and that some tribes may not be focused on homeownership today. While many Native nations traditionally had strong concepts of home and homeownership in the past, today tribal members (and leaders) may see homeownership as complicated, overwhelming, and hard to achieve.

In this course, we will break down the different components of homeownership, looking at what it takes and how we can build on traditional concepts of homeownership to expand culturally appropriate homeownership in Native communities.

As we begin this discussion, let’s look at what homeownership means to you.

What does homeownership mean to you?

Hearing from Homeowners

Hearing from Homeowners

Now, let’s hear from some Native homeowners in South Dakota.

As you listen to the homeowners, are there any concepts of homeownership that you’d like to add to the list we’ve made above?

These are some of the key reasons we promote homeownership. In this course, we’ll look at why homeownership makes sense for individuals and families, and why it makes sense for tribes and communities.

Native Concepts of Homeownership

In laying the foundation for our work together, we also want to look at how Native communities have traditionally viewed homeownership. Homeownership has been central, for example, to some pueblos in the Southwest. While other tribes were traditionally nomadic, there was always a base — always a place that was “home.”

How did your community traditionally view the concepts of home and homeownership? How were communities designed? What values did these communities reflect?

What does housing look like now in many Native communities? What values does this housing reflect?

VISIONING FOR THE FUTURE

Later in this course, we’ll start designing communities, exploring how we’d like our neighborhoods and communities to look in the future. But for now, let’s share the values we’d like our visioning for the future to reflect.

What values are reflected in the housing and neighborhoods you’d like to see in the future?

How Did We Get to Where We Are Today?

How Did We Get to Where We Are Today?

In order to understand where we are today, it’s important to look at history.

As we look at history, we’ll develop a timeline. First, we’ll take a look at an overview of historical policy eras developed by the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI).

Tribal Nations and Other American Governments Through History

Note: Content is drawn from “Tribal Nations and the United States,” National Congress of American Indians, 2015, pages 13-14.

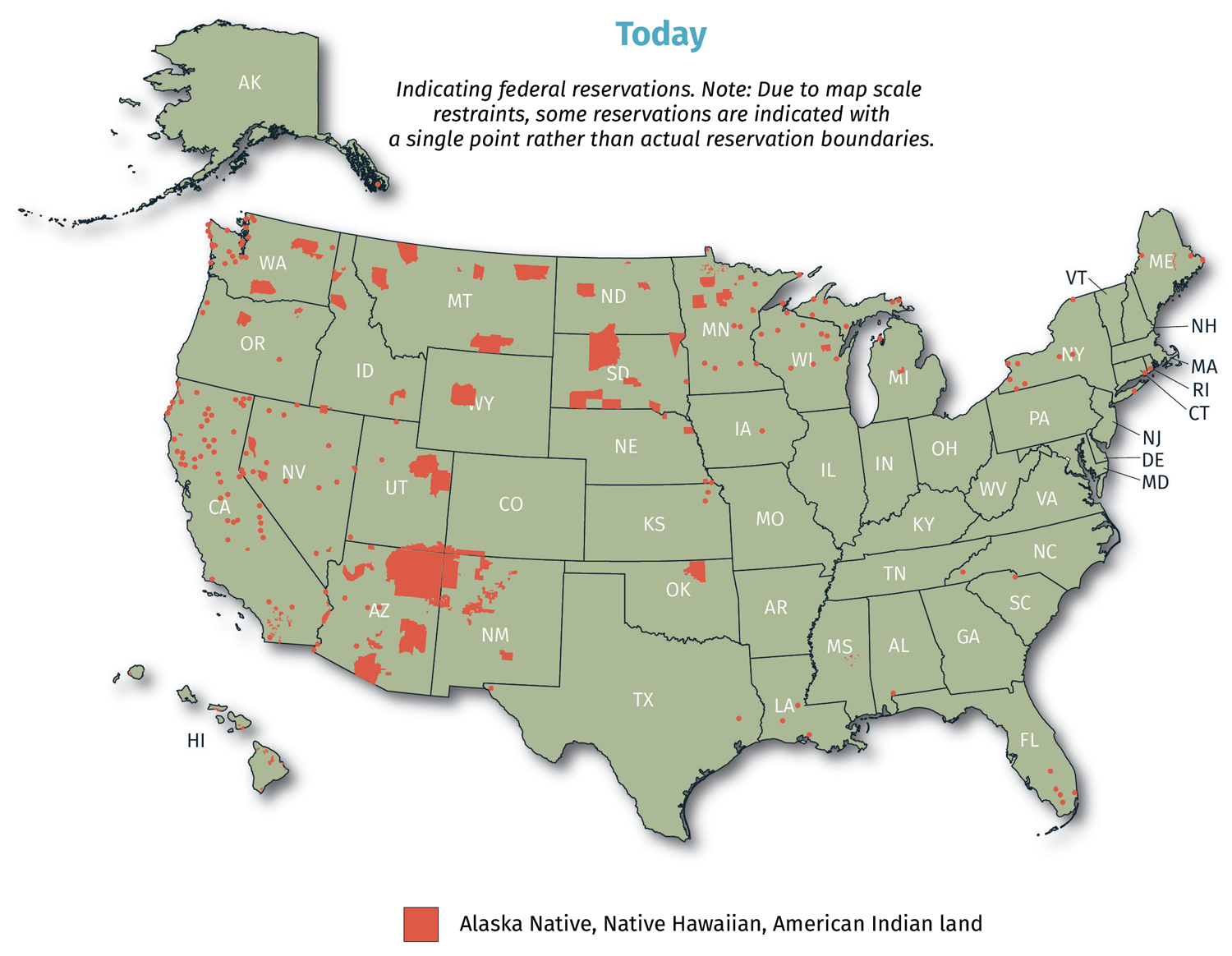

This summary of major federal policies is by no means an exhaustive chronology. It informs on the actions of the United States government in dealing with Native peoples of each of the 50 states, now known as the United States. There are three Indigenous peoples recognized by the federal government:

American Indians – 48 States

-

◉Federally recognized as Native peoples and governments

-

◉Membership determined by American Indians themselves

National Organization Dedicated to Self-Governing Tribes – NCAI

Alaska Natives – 49th State

-

◉Federally recognized as Native peoples and governments

-

◉Membership determined by Alaska Natives themselves

National Organization Dedicated to Self-Governing Organizations – AFN

Native Hawaiians – 50th State

-

◉Federally recognized as Native peoples under two categories:

-

Native Hawaiian – Natives of any Blood Quantum

-

Native Hawaiian – Natives of 50% or more blood quantum under the HHCA

-

-

◉Federal recognition of a Native Hawaiian government is yet to be determined

-

◉Federally defined Homestead Associations have been established

National Organization Dedicated to Self-Governing Homestead Associations – SCHHA

Now, we’ll zoom in on key elements of the history of housing in Native communities:

Housing

Housing

For many tribes, housing for tribal members means “low-rent,” affordable rental housing for low-income tribal members. Insufficient funds for low-income members and little or no available mortgage credit for moderate-income members have led to severe overcrowding and affordable housing shortages in many Native communities.

- ◉Since 1962, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has provided funding to Indian Housing Authorities (IHAs) in American Indian and Alaska Native communities.

- ◉Before NAHASDA was enacted in 1996, there were two primary sources of funding for tribal housing: 1) operations/admin and 2) development.

-

◉This funding assistance was restricted to low-income tribal members and could not be used to provide services to moderate-income tribal members.

-

◉The Low Rent and Mutual Help Programs created a prescribed development process with limited vision for creative or culturally appropriate site and housing design.

-

◉The federal government focused on quick fixes and built housing, which at the time, was better than what communities had, but they seldom focused on crucial resident education or housing maintenance issues.

-

◉Because available funding was inadequate, Indian Housing Authorities could not build enough homes to meet the housing needs of their communities, could not maintain the homes they did build, and had to disregard sustainable and traditional designs and layouts.

-

◉Often, the only homes available to tribal members were small box-shaped houses, often located on scattered sites or in unattractive subdivisions.

-

◉For tribal members who could afford to buy a home, there was virtually no homeownership market, private development, or mortgage lending available on reservation lands.

-

◉In this environment, moderate-income households faced difficult choices: they could buy a mobile home, try to build their home without mortgages (often with exorbitant interest), or move off the reservation.

Changes Through NAHASDA

Changes Through NAHASDA

Enacted in 1996, NAHASDA is part of a broad movement to support tribal sovereignty and community- specific decision-making. NAHASDA replaced several previous housing programs, offering tribal governments more options to expand their housing programs and create community-based homeownership opportunities. Although NAHASDA funding levels have always been too low to fully address housing shortages, they allow tribal governments to:

-

◉Design housing programs better suited to their members.

-

◉Leverage federal dollars with private funding.

-

◉Set aside a portion of funding for higher-income families in need of housing.

The ability to leverage government subsidies together with banks and private investment is key to building more and better homes for tribal members.

While NAHASDA is still focused on low-income households, tribes can use NAHASDA funds to leverage government-guaranteed and conventional loans for homeownership, thereby providing more housing options to members across income levels.

Moreover, by leveraging NAHASDA funding, tribes can create mortgage programs that allow households to enlarge existing homes, renovate deteriorated houses, or refinance mobile homes at reduced interest rates or for longer terms.

In addition, Tribally Designated Housing Entities (TDHEs) and programs can use up to 10% of their Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG) funds for mid- to above-income households, but there is a process and documentation is required. Often, tribes use the money for their low-income renters, and it is difficult to determine who to assist with the 10% allocation.

In addition to seeing NAHASDA funding in the 1990’s, some tribes also began developing Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) units, which also target very low-income families. Because of LIHTC income limits, in order to occupy the unit, families must document their low-income status.

This current reality is our starting point. In this course, we’ll talk about how to move from this reality to create opportunities that provide the benefits of homeownership that we have discussed and heard about. We also want to keep in mind the concepts of home and homeownership that have been the traditions of Native nations for centuries. Providing homeownership opportunities is a strong expression of sovereignty, as tribes identify the best way to provide housing for their citizens. This often means a shift in mindset for many Native peoples, which we will discuss in the modules ahead.

As part of our overview of the history of housing and homeownership in Native communities, let’s take a look at a historical retrospective on homeownership in Indian Country, developed by the Center for Indian Country Development.