MODULE 3: Navigating Land Issues

ENHANCING AND IMPLEMENTING HOMEOWNERSHIP PROGRAMS IN NATIVE COMMUNITIES

Navigating Land Issues

Navigating Land Issues

Navigating land issues is a critical piece of the homeownership process for many Native families, as much of homeownership lending for Native families is impacted by the trust land status of potential sites within reservation boundaries. Typically, off reservation, the lender provides a mortgage loan to the homebuyer to enable them to purchase a home. The collateral for this loan is the house and the land, so if the borrower fails to make payments, the lender has the right to the house and the land. The mortgage process is different on trust land, since the land cannot be used as collateral. On trust land, the lender takes a leasehold mortgage, where the collateral for the loan is the house and the interest in the land, rather than the land itself beneath the house.

The Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership preface provides an overview of this history of Indian land on pages 14-17. Today’s land processes and issues are a direct result of the historical policies we discussed in the previous module. Now, we’ll take a look at land ownership status and the leasehold process.

Review: Why Is Indian Land Held in Trust?

Review: Why Is Indian Land Held in Trust?

The trust land status may be tracked back to the Supreme Court case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, one of the three cases that comprise the Marshall Trilogy.

In this case, the Cherokee Nation was trying to stop the State of Georgia from forcibly removing the tribe from traditional lands. Chief Justice John Marshall found that:

-

◉Indians were not foreign nations, but “domestic, dependent nation[s]” – small nations that have accepted the protection of a larger nation, yet still retain their sovereignty.

-

◉The “duty of protection” means that the United States, because it asserts ownership over Indian lands, must protect Indians from all hostiles, including hostile U.S. citizens.

-

◉The “guardian/ward relationship” means that the U.S. holds all land and resources in trust for the Indians, creating a fiduciary duty.

Impact of the Allotment Act

Impact of the Allotment Act

As we saw in the previous module, the Allotment Act enacted in 1887 divided reservations into individual parcels and assigned these parcels to individual families. Over generations, more and more heirs inherited these parcels, complicating the process of accessing land for development. The impact of the Allotment Act over time is illustrated in the chart below.

Land Ownership Status

Land Ownership Status

Today, there are three main types of land title and ownership on reservations as a result of federal land policies:

-

◉Tribal trust land. Much of the land within the boundaries of a reservation is “tribal trust land”— held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of current and future generations of tribal citizens. In order to put a structure on this land, it must be leased from the tribe.

-

◉Allotted trust land. Because of the allotment policy (where allotments of trust land were given to individual citizens), a significant amount of trust land is held in trust for individuals. If an individual tribal member wants to use a parcel of allotted land (to build a home, for example), this individual must obtain the permission (signature) of all or some of those who have rights to this allotment. Since multiple generations have been born since the original allotment policy was carried out, one parcel of land may have hundreds of people who have rights to that parcel. While historically permission for a specific use of the land needed to be obtained from each person with a stake in a parcel, recently, a number of tribes have enacted policies to allow for percentages of signatures less than 100% of allotment co-owners.

-

◉Fee simple land. Fee simple land is the most common land ownership model in the United States outside of reservation boundaries and refers to land that is not held in trust status. Much of the fee simple land within reservations was taken out of trust status, but may now be owned by the tribe, a tribal member, or a non-tribal member.

The combination of different types of land ownership within the boundaries of a single reservation often results in “checkerboarding,” which describes the pattern when different types of land are mixed together.

The Leasehold Process

The Leasehold Process

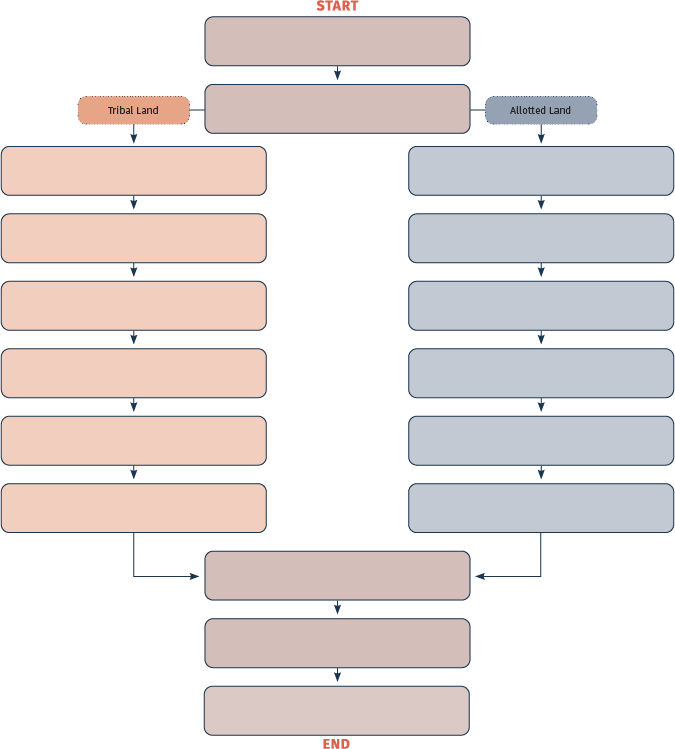

Since trust land can’t be used as collateral, mortgages on trust land are structured differently. Supporting homeowners often means helping to navigate the leasehold process. What are the steps to obtaining a leasehold? Who is involved? Often, a prospective homebuyer needs to go through certain steps at the local level through the tribe and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and then the local BIA needs to send documents to the regional BIA office for recording.

Let’s take a look at a sample leasehold process from the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. What strikes you in reviewing the process?

Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe (CRST) Leasehold Process

What does your tribe’s leasehold process look like?

Title Status Reports

As we see in the Cheyenne River process, having a certified TSR is the ultimate goal of the leasehold process. The TSR is critical, because it shows who is leasing the land, as well as other elements impacting the tract of land, including easements, rights of way, and mineral rights. Since the certified TSR is issued by the regional BIA office, delays in issuing it may stall the entire loan process. The timeline for obtaining the certified TSR varies from BIA region to region.

Environmental and Cultural Preservation Reviews

Environmental and Cultural Preservation Reviews

The environmental and cultural preservation reviews are also a vital part of the leasehold process to ensure that proposed development does not impact cultural or environmental sites. It’s important to determine who conducts these reviews in your community and how long the process may take. Depending on the timeline and staffing, these reviews may also significantly impact the leasehold timeline.

Expediting the Leasehold Mortgage Process

Expediting the Leasehold Mortgage Process

As we’ve seen, the leasehold mortgage process can be quite complicated and time-consuming, and it may be seen as an obstacle to homeownership. It’s important to note two strategies that may simplify and expedite the process.

- The HEARTH Act (Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Homeownership)

In 2012, Congress passed the HEARTH Act, which allows tribes to lease restricted lands for residential, business, public, religious, educational, or recreational purposes without the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. This authority has the potential to significantly reduce the time it takes to approve leases for homes in Indian Country. As of March 8, 2018, the BIA has approved regulations submitted by 39 tribes to manage their own leasing for homeownership. The Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership provides a case study which describes the efforts of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin to implement the Act.

What are the advantages in implementing the HEARTH Act?

What are the challenges in implementing the HEARTH Act? Why aren’t more tribes doing it?

-

Compacted Tribal Land Management System

A number of tribes have compacted with the BIA to take their land management processing (including Land, Title, and Records) in-house. The Salish and Kootenai tribes, for example, have compacted land management, bringing it in-house.