MODULE 8: Homeownership Development: Planning to Drive Change

Homeownership Development: Planning to Drive Change

Homeownership Development: Planning to Drive Change

As we’ve discussed from the outset, homeownership development means comprehensive planning. We’ve seen that there are many different pieces of the homeownership puzzle – including needs assessments, community input, preparing homeowners – that must be coordinated.

Ideally, homeownership development should be part of a master planning process. What else does the community have in place that relates to future homeownership sites and opportunities? Where are schools, stores, and health care facilities? What else does the community want, such as community facilities, recreational areas, retail space, community gardens?

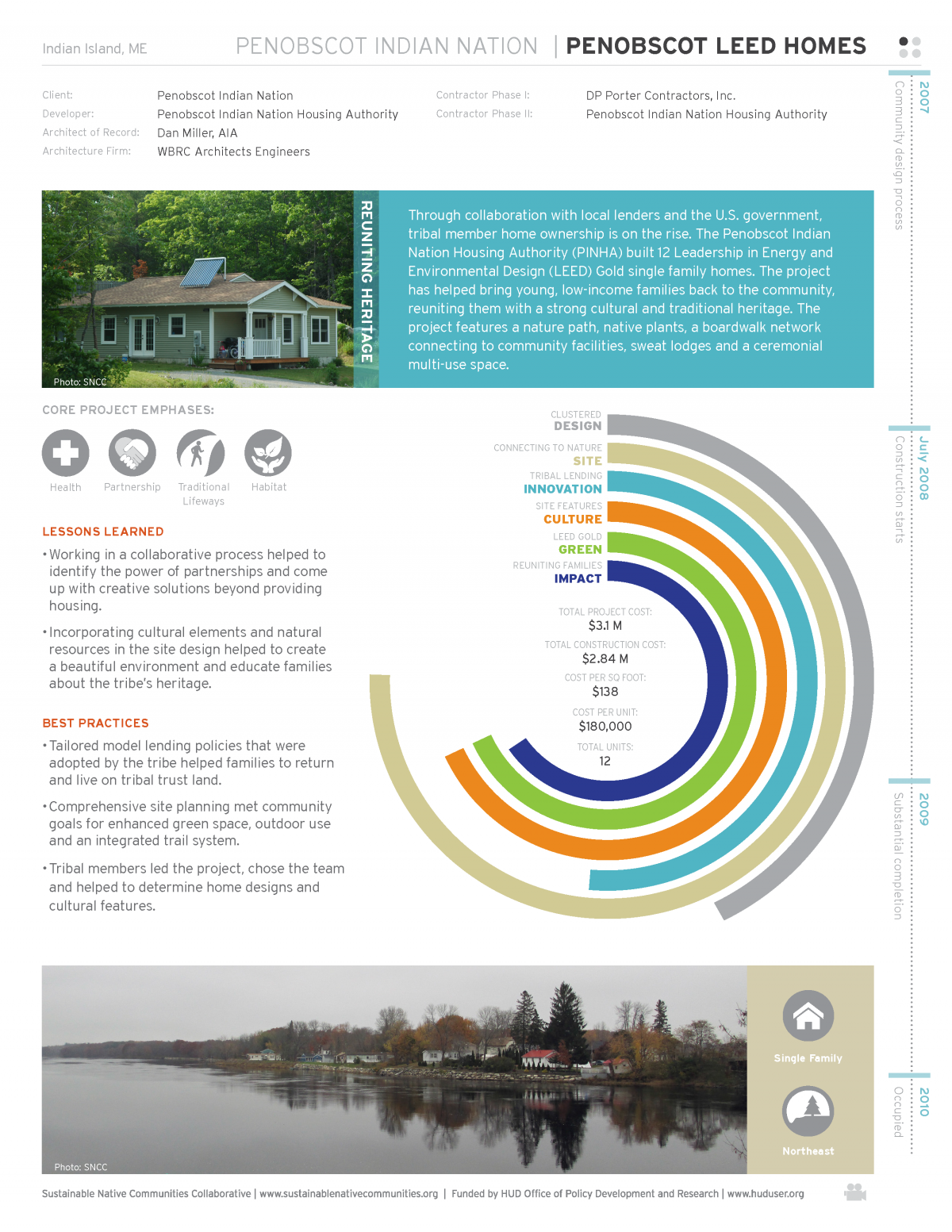

As we explore comprehensive planning, let’s take a look at the efforts of the Penobscot Nation in Maine.

What struck you about the efforts of the Penobscot Nation?

The Planning Team

The Planning Team

While the planning process needs to have strong leadership with vision, it also requires different expertise, including technical expertise.

What professionals do you need on the planning team?

You should consider including the following on your planning team:

-

◉Community members

-

◉Architect

-

◉Engineer

-

◉Land expert

-

◉Infrastructure expert

-

◉Construction manager

-

◉Resource developer (to develop funding applications)

Often, we may wait to pull in an architect and engineer until we feel like we’re “ready” for their expertise – when it’s time to develop floor plans or site maps. Rather than waiting, it’s recommended that you involve your architect and engineer in your planning from the outset. Thoughtful design from the outset can help cut down costs by offering creative solutions to meet needs while lowering costs and preventing expensive add-ins after the fact that were initially overlooked.

As we discussed in exploring who can conduct a housing needs assessment, it’s important to make sure that these professionals are a good fit for your organization. Beyond their technical expertise, it’s important to make sure that they understand your organization and community priorities, and can work well with your staff.

How can you find the right members of your team and make sure they’re a good fit?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Healthy Native Homes Roadmap Developed by Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative and Enterprise Community Partners

The Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative (SNCC) focuses on culturally and environmentally sustainable development with American Indian, First Nations, and Indigenous communities.

The Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative (SNCC) focuses on culturally and environmentally sustainable development with American Indian, First Nations, and Indigenous communities.

Through planning, architectural design, technical assistance, and research, SNCC’s services help tribal communities gain self-sufficiency, improve their impacts on the natural world, and develop healthy, green, culturally responsive communities.

One of the valuable resources that SNCC has developed in partnership with Enterprise is the Healthy Native Homes Roadmap, a short online guide that asks questions and provides recommendations for new tribal housing projects.

Go to Healthy Native Homes Roadmap.

The roadmap looks into the five phases of development:

-

◉Concept Phase

-

◉Pre-development Phase

-

◉Development Phase

-

◉Construction Phase

-

◉Operations Phase

Four competencies are utilized in the roadmap to navigate the development process:

-

Project Management evaluates organizational capacity needs.

-

Community + Residents considers outreach and training plan.

-

Budget + Funding Sources helps navigate financing.

-

Design + Construction outlines core competencies to build the project.

Planning for Neighborhood or Scattered Site Development

Planning for Neighborhood or Scattered Site Development

Homeownership development in tribal communities is typically carried out in two ways:

-

1. Scattered site development

-

2. Neighborhood or subdivision development

It will be important to determine which development approach is best for your project. Part of this will depend on families’ preferences – where do families want to live? Let’s take a look at some of the differences between scattered site and neighborhood/subdivision development:

|

SCATTERED SITE DEVELOPMENT |

NEIGHBORHOOD/SUBDIVISION DEVELOPMENT |

|

|

Description |

In this method, building sites are scattered in different locations. |

In this method, building focuses on building a certain number of homes in a neighborhood or community design, in proximity to one another. |

|

Homebuyer Preferences |

Families may indicate that they prefer scattered site development because they would like to live “out in the country” or on allotted land that belongs to their family. |

Because much of the affordable housing in tribal communities was built by THE Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Housing Authorities in “housing clusters,” families may have a negative association with the subdivision/ neighborhood concept. |

|

Infrastructure |

With scattered sites, it is often necessary to provide new infrastructure at each site, including roads, electricity, wells, and septic. This often results in more costs for the homebuyer. |

With the neighborhood/subdivision, infrastructure is provided in bulk for the entire community. It may be possible to build a lagoon for waste for example, rather than have individual septic tanks, or to hook up to one main water line, rather than dig individual wells. Building this way saves overall costs and often results in lower costs for each homebuyer. |

|

Land |

With scattered sites, is it often necessary to obtain individual leases for each site, which may be time consuming and lead to barriers. |

With the neighborhood/subdivision, it may be possible to work with one master lease and individual assignments, which streamline the leasehold process. |

|

Cost |

Infrastructure costs often make scattered site development more costly for homeowners. There are also additional costs in construction of homes in a larger geography, such as material delivery to multiple sites. |

Infrastructure costs are often lower in neighborhood/subdivision developments, and centralized building can also reduce costs. |

In exploring the differences between scattered site and neighborhood development, it is important to look at the distinctions through the lens of your organization’s mission. If your Tribally Designated Housing Entity’s (TDHE’s) mission is to serve the housing needs of as many tribal citizens as possible, are you able to fulfill this mission by building in scattered sites?

Infrastructure Development

As we saw in our discussion about the differences between scattered site and neighborhood development, infrastructure development is a key piece of development in many rural Native communities. Unlike urban areas, where new construction can focus on building a new structure and tying in to existing infrastructure, housing development in many Native communities often means building new infrastructure on raw land. This may mean all new water lines, wastewater services, electrical lines, phone lines, and roads. Since including the cost of new infrastructure may put homeownership out of the reach of many potential homeowners, it is important to work to identify sources to subsidize these costs, such as:

◉Indian Health Service (IHS) – water/wastewater

◉USDA Rural Development – water/wastewater

◉Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) – roads

◉Tribal governments

Planning Timeline

Planning Timeline

Comprehensive planning also includes developing a detailed, realistic timeline, based on estimates for each element of the project. How long can we estimate that the needs assessment will take, for example? If we start the needs assessment in June 2019, when can we project that it will be complete? What about the other elements? Finally, when can we estimate project completion?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

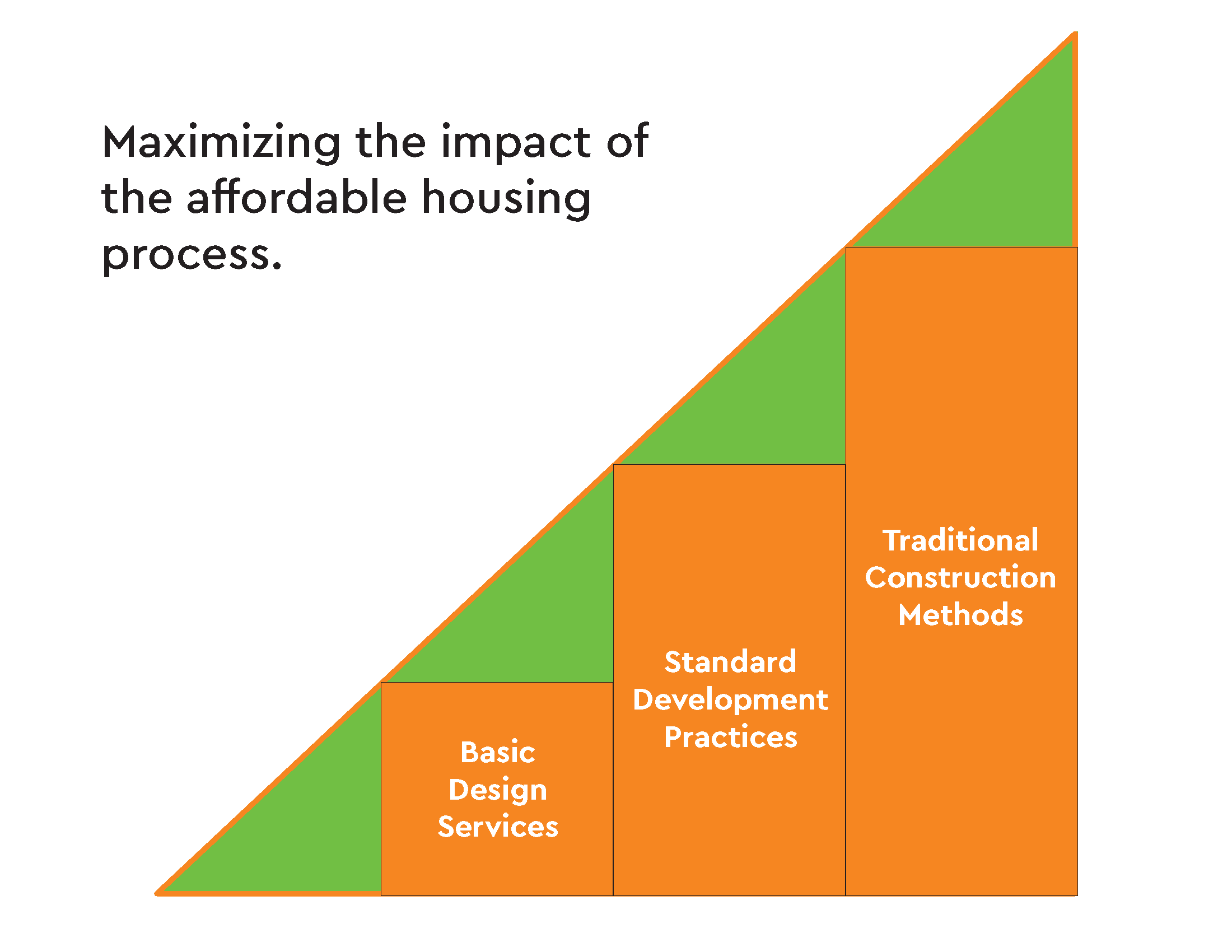

Optimizing the Impact of Affordable Housing Delivery

Developed by Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative

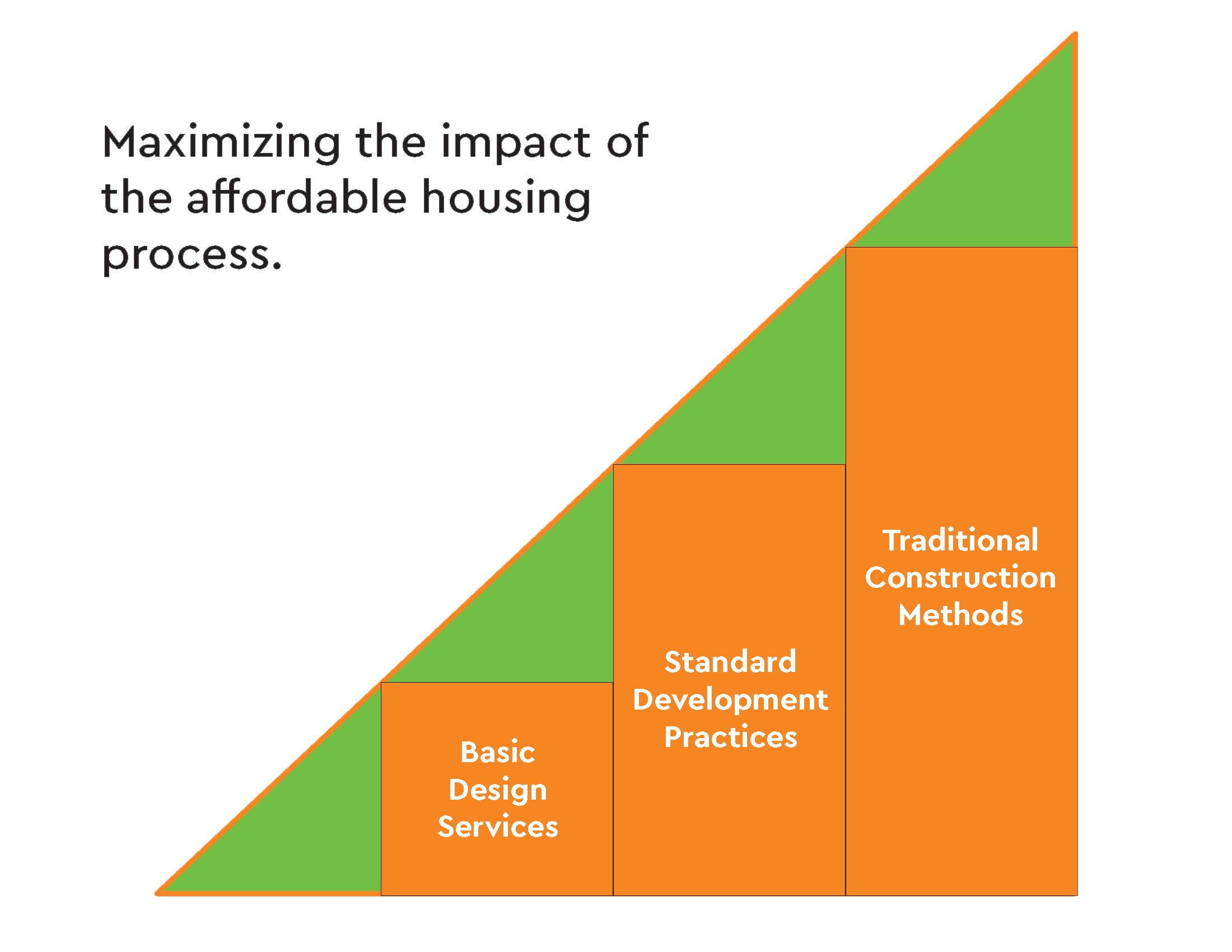

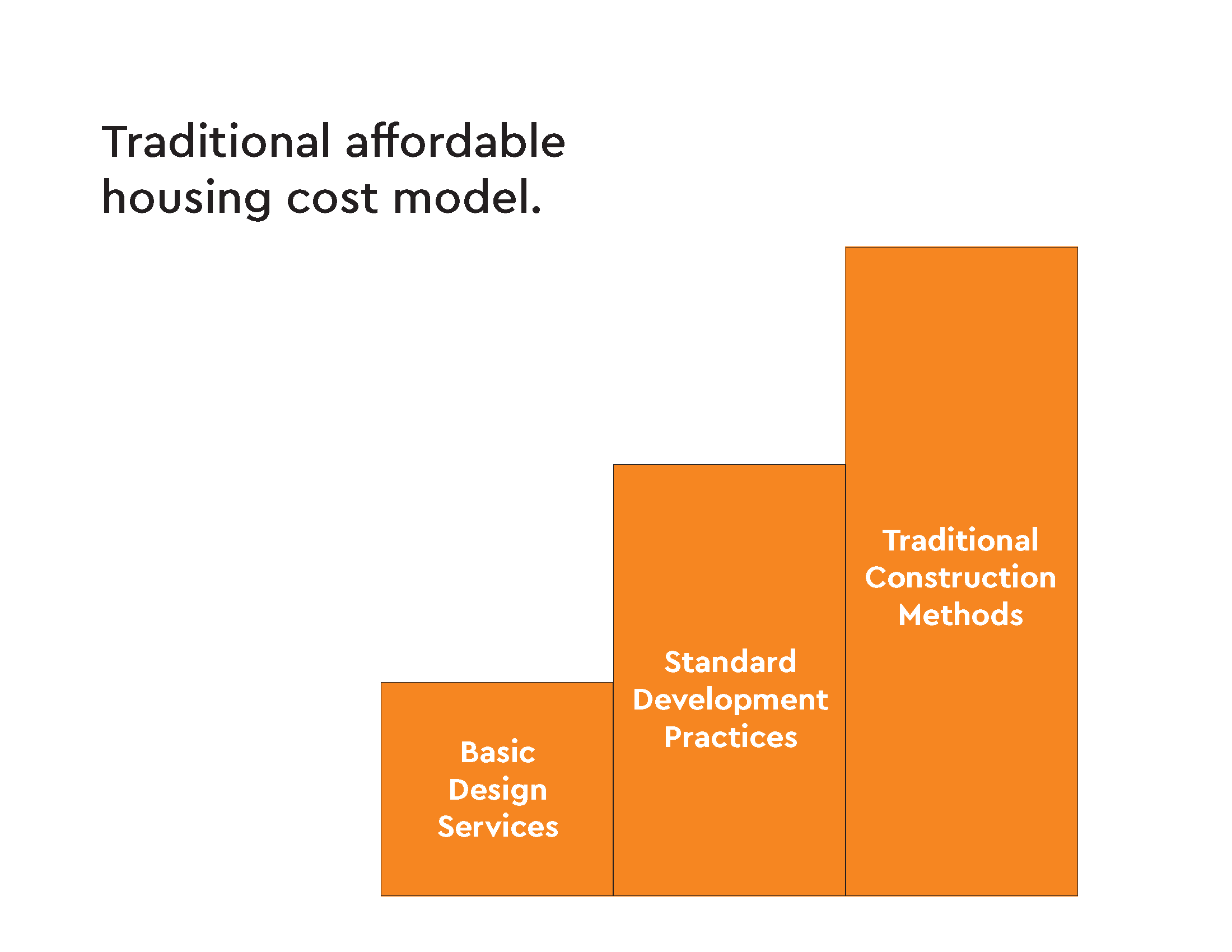

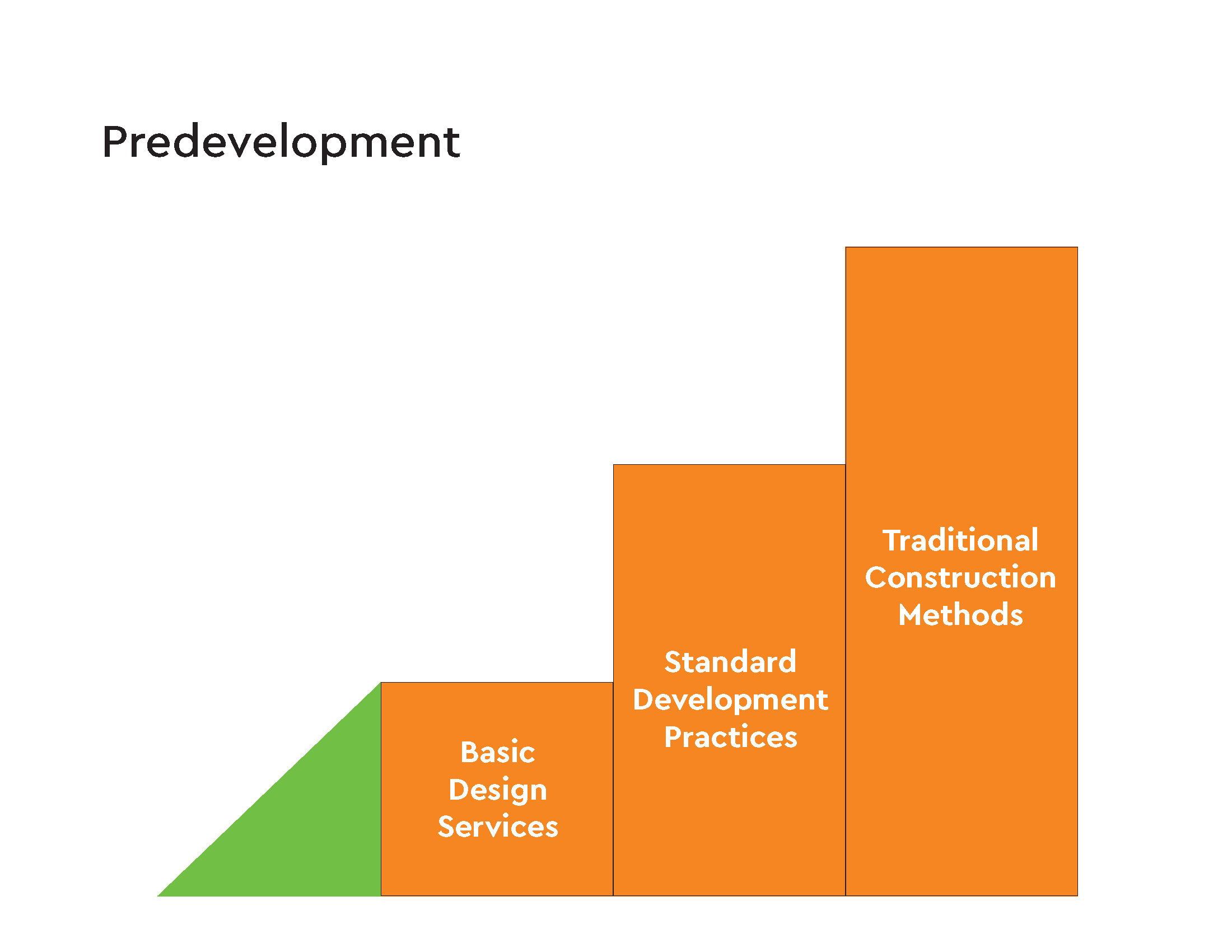

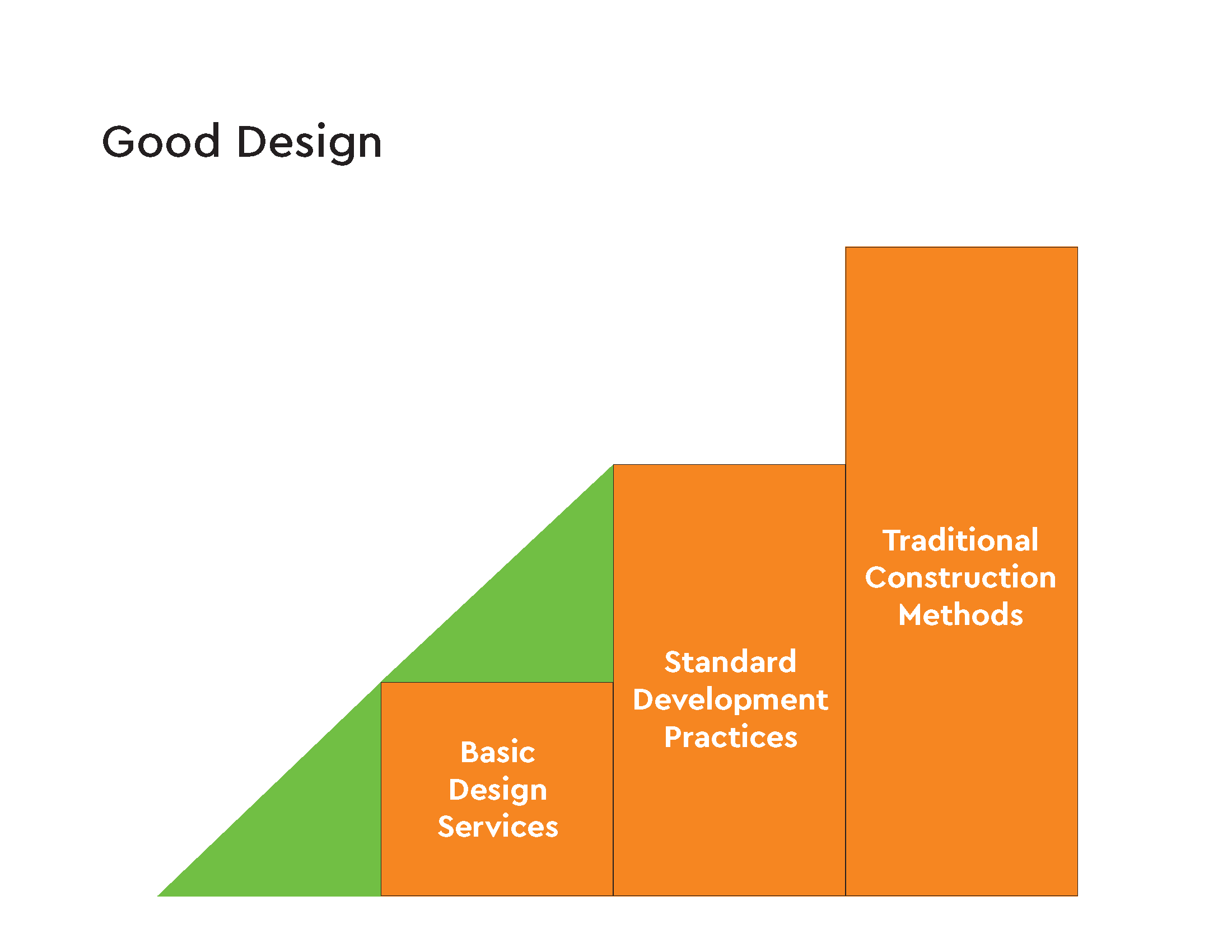

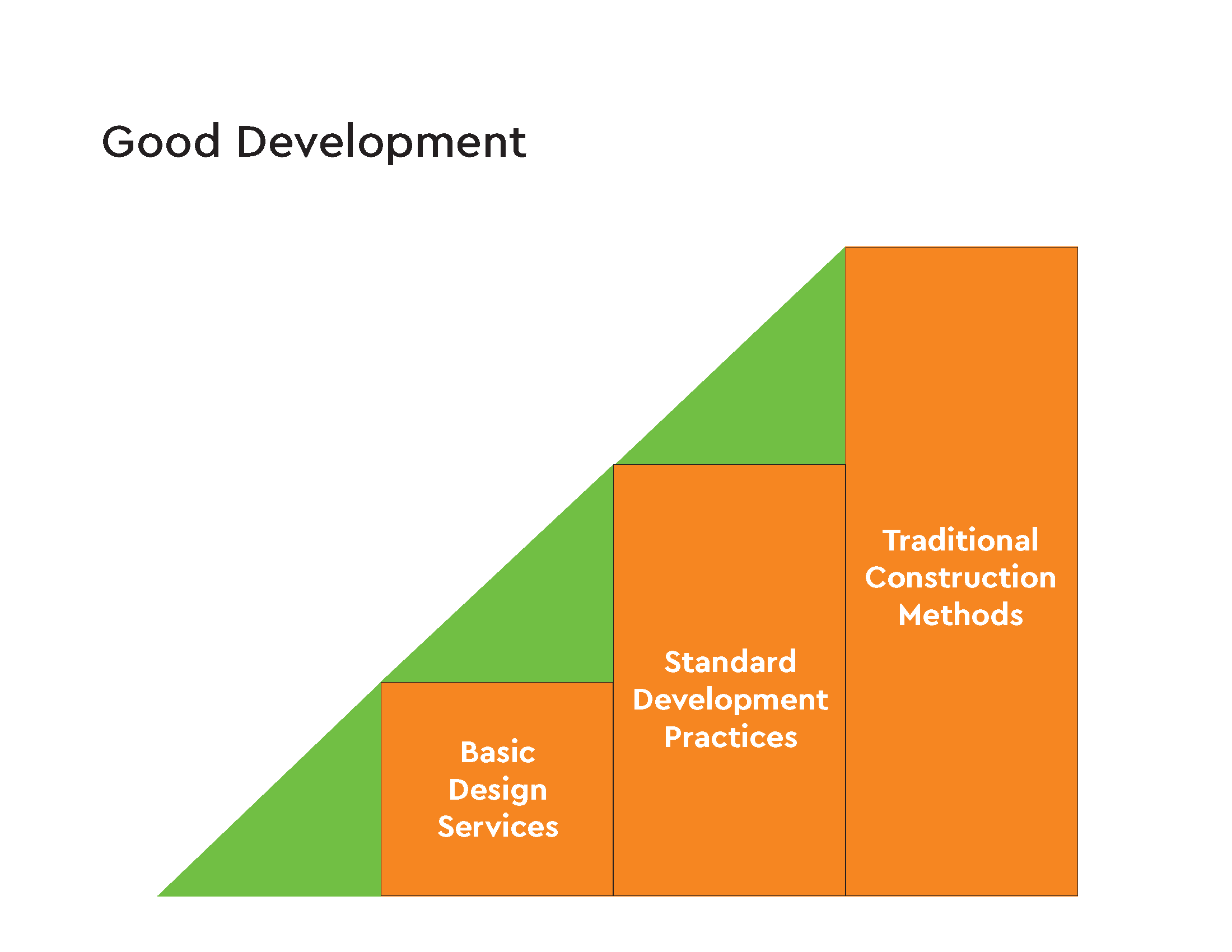

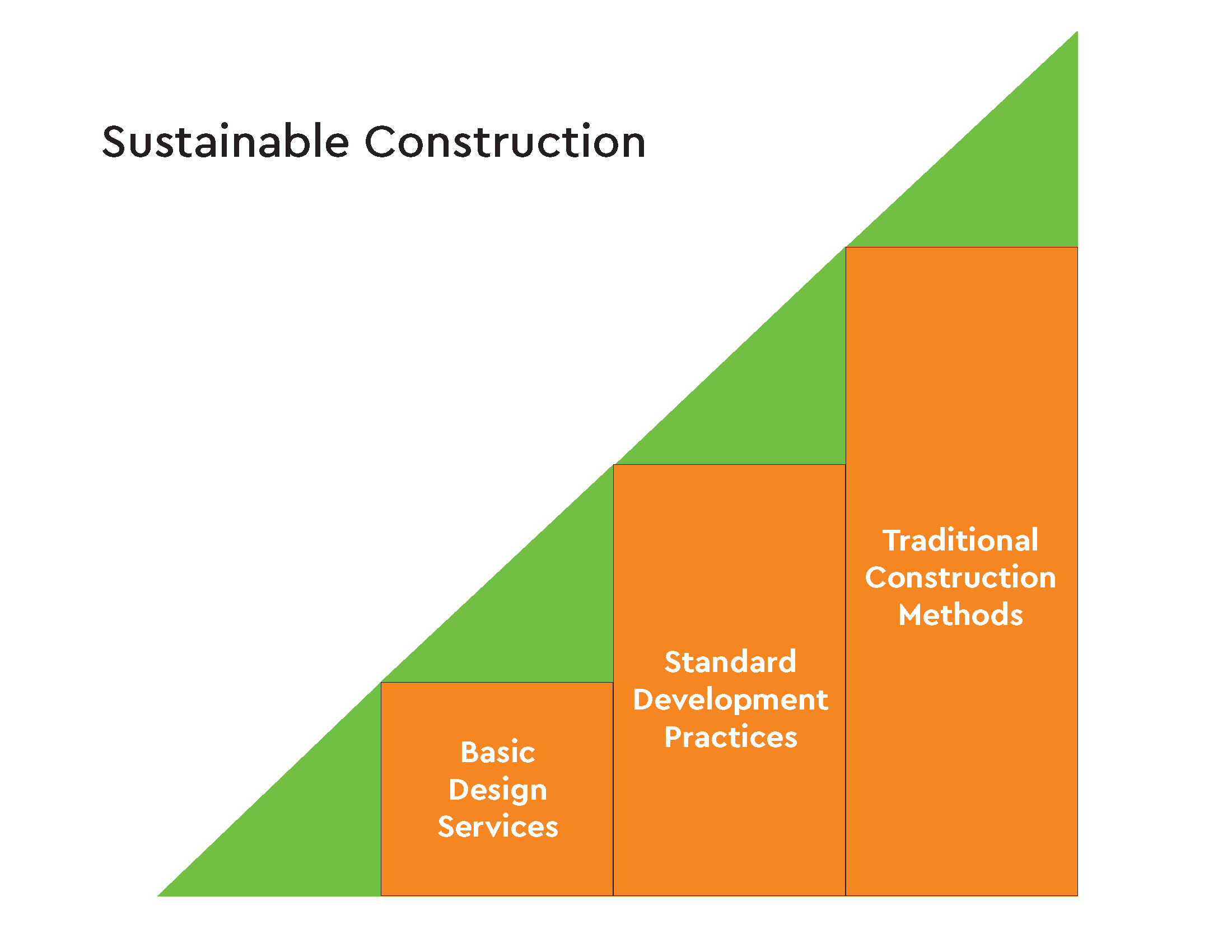

In working with development financing, the Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative (SNCC) has developed a model that illustrates the different phases of development. This model recognizes the relationships between time, cost, and quality based on two different approaches to project delivery, highlighting the value of pre- development and comprehensive design services. The big idea is that additional time and funding for each phase, from pre-development, through good design, development, and sustainable construction are necessary to achieve exemplary results for the marginalized populations these projects will be serving.

The rectangular columns represent a basic project delivery approach utilizing standard practices. The triangular areas represent the positive impacts of additional time and budget that are typical precursors to exemplary design and construction outcomes. The areas shown in the diagram represent conceptual observations and are not meant to be representative of relative costing or timing, which will vary widely across projects.

Any development process can arrive at a higher goal by incorporating a fractional amount of time and resources during the pre-development design phase. The top right point suggests a built outcome that has more value than conventional delivery results in terms of sustainability, cultural responsiveness, and the numerous added efficiencies and health benefits that exemplary architecture brings. The takeaway from this diagram is that each of the triangles is crucial to reach higher development performance goals. If any green triangle is missing, the project results may only reach the level of conventional construction.

For example, pre-development and good design goals may be reached for a given project, yet if good development and sustainable construction practices are not built into the process, the fruits of the pre-development and design work will not be implemented in the completed project. This visual argument for a value-added development process can help decision-makers, owners, and developers to understand the choices, time, and money involved in achieving exemplary built results.

Copyright © 2019 Nathaniel Corum + Joseph Kunkel www.sustainablenativecommunities.org

Development Financing

Development Financing

Financing is also a critical piece of the development puzzle, and securing this financing is one of the first steps in the development timeline. Tribes, TDHEs, and other developers can access a number of financing sources to develop land and construct housing. Typically, these funds are borrowed by the developer, and then repaid as tribal members secure mortgage financing for individual homes within a given development project. This debt structure is an important part of the homeownership development process. Unlike grant funding, in which finite funds are gone once the grant is expended, through debt financing, the TDHE or developer gets their investment back as families purchase homes with individual mortgages.

Sources of development financing include:

|

DEVELOPMENT FINANCING RESOURCE |

BRIEF DESCRIPTION |

|

Capital Magnet Funds |

The Capital Magnet Fund is administered by the Treasury Department’s Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund and provides grants to CDFIs and qualified nonprofit housing organizations through a competition. The funds can be used to finance affordable housing activities, as well as related economic development activities and community service facilities. |

|

Indian Community Development Block Grant (ICDBG) Funds |

Tribes and TDHEs are eligible for ICDBG funds, which may be used for housing development. |

|

Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG) |

The IHBG is a formula grant to tribes and TDHEs to provide a range of affordable housing activities, including housing development on Indian reservations and Indian areas. The block grant approach to housing for Native Americans was enabled by the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act of 1996 (NAHASDA). |

|

Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) |

The LIHTC provides funding for the development costs of low-income housing by allowing an investor to take a federal tax credit equal to the cost incurred for development. LIHTC credit properties are often rental properties for very low-income families but may be structured as rent-to- own units. |

|

Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant (NHHBG) |

The use of NHHBG funds is limited to eligible affordable housing activities for low-income Native Hawaiians eligible to reside on Hawaiian home lands. The Hawaii State Department of Hawaiian Home Lands (DHHL) is the sole recipient of NHHBG funds. Development activities that are currently being implemented by DHHL include site improvements for new construction of affordable housing. |

|

New Market Tax Credits (NMTC) |

The NMTC Program incentivizes community development and economic growth through the use of tax credits that attract private investment to distressed communities. |

|

HUD Section 184 |

Tribes, individual tribal members, and TDHEs are eligible to borrow funds for development from approved HUD Section 184 lenders. |

|

State Housing Finance Agency Funds |

State housing finance agencies may have funding available for housing development, including federal funds (such as HOME funds) or state housing trust funds. |

|

Title VI |

HUD provides Title VI loans for development to tribes and TDHEs. The purpose of the Title VI loan guarantee is to assist IHBG recipients (borrowers) who want to finance additional grant-eligible construction or development at today’s costs. Tribes can use a variety of funding sources in combination with Title VI financing, such as low-income housing tax credits. Title VI loans may also be used to pay development costs. |

|

Tribal Funds |

Tribes may elect to designate a portion of their funds for housing development costs. |

| State Housing Finance Agency |

State housing finance agencies may have funding available for housing development, including federal funds (such as HOME funds) or state housing trust funds. |

|

Title VI |

HUD provides Title VI loans for development to tribes and TDHEs. The purpose of the Title VI loan guarantee is to assist IHBG recipients (borrowers) who want to finance additional grant-eligible construction or development at today’s costs. Tribes can use a variety of funding sources in combination with Title VI financing, such as low-income housing tax credits. Title VI loans may also be used to pay development costs. |

|

Tribal Funds |

Tribes may elect to designate a portion of their funds for housing development costs. |

Community Input

Community Input

Looking at the planning process, it’s important that development efforts build on community input. Incorporating community input and engagement into the design process is another critical factor in achieving the benefits of quality design. Community participation will bring a better understanding of the needs, barriers, and desired opportunities of the residents and surrounding community. By having a deeper understanding of the functions and program of the building, the design can more accurately reflect the necessities of use and experience.

What are some ways to gather community input?

The Charrette: A Design Planning Workshop

The Charrette: A Design Planning Workshop

One design tool, a charrette, brings together a diverse group of stakeholders to establish goals, identify strategies, discover synergies, and create a roadmap for ongoing implementation. This workshop can help set a development project on the path to success. Holding a charrette is a critical first step in establishing an effective integrative design process. Integrative design incorporates sustainability into the property from the very beginning, using a holistic approach to promote culture, healthy living environments, resource conservation, and sustainability throughout the development’s lifecycle.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Online Toolkits

Developed by Enterprise Community Partners

Enterprise has developed multiple resources to help incorporate design into a project, from pre- development design to a charrette toolkit to a participatory design toolkit.

Design Matters Toolkit

Enterprise’s Design Matters Toolkit provides industry-tested tools that allow developers to incorporate thoughtful, people-focused design into any affordable housing project – no matter how tight the budget or complex the timeline.

Go to the Design Matters Toolkit.

Community Design Workshop Activity

Community Design Workshop Activity

In this activity, we’ll work in small groups to design a community development. Each group will work with these common parameters:

-

◉20-acre parcel

-

◉Three miles from a school

-

◉Next to existing water infrastructure

-

◉Access road exists

With these parameters in mind, groups will work to design their community housing projects, with the following questions in mind:

-

◉How many homes will you include?

-

◉Will you have only single-family homes or include multi-family units?

-

◉What amenities will you include beyond housing?

-

◉Will your project reflect traditional community design concepts and cultural elements?

-

◉Will your project feature green or sustainable materials, systems, and design approaches?

-

◉How will the special needs of elders, children, and the mobility impaired be addressed in your process?

Once each group has designed their community project, they will share with the large group. Once we’ve learned about each design, everyone will vote to determine the favorite community design.

REFLECTIONS

-

◉What struck you in this activity?

-

◉What would it take to do this in your community?

Looking at Sample Community Designs

Thunder Valley Regenerative Community

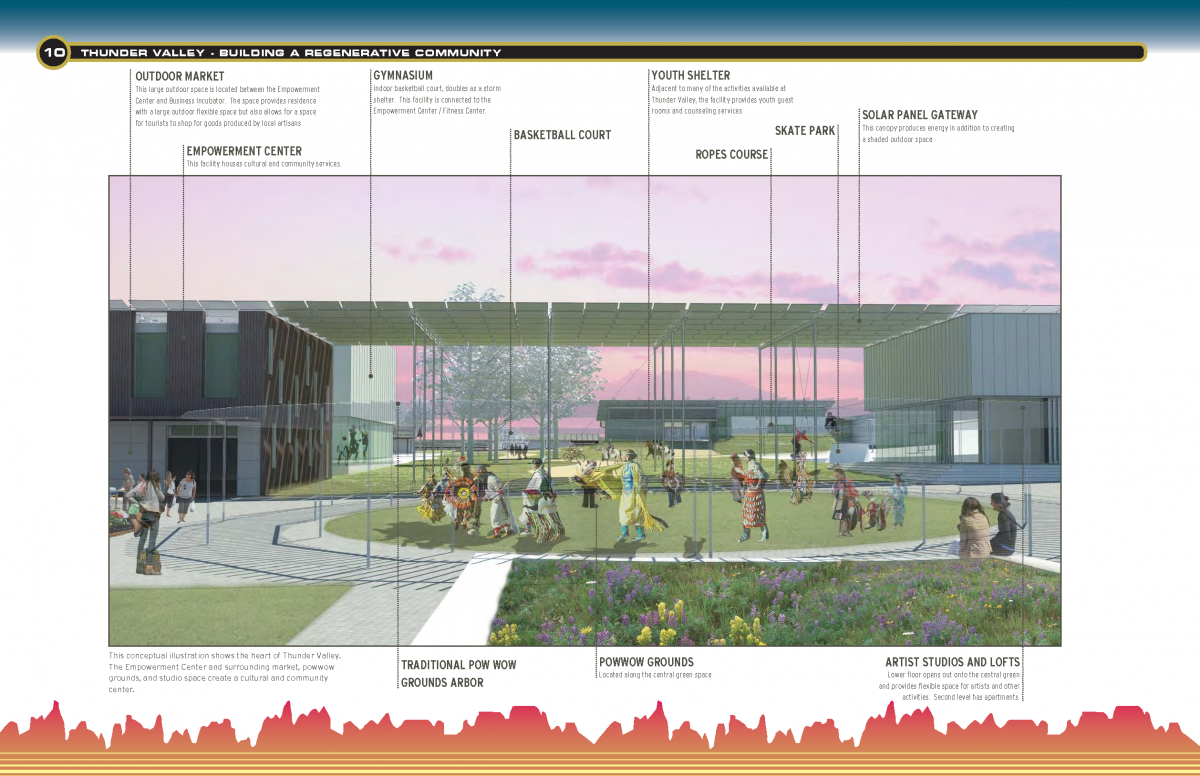

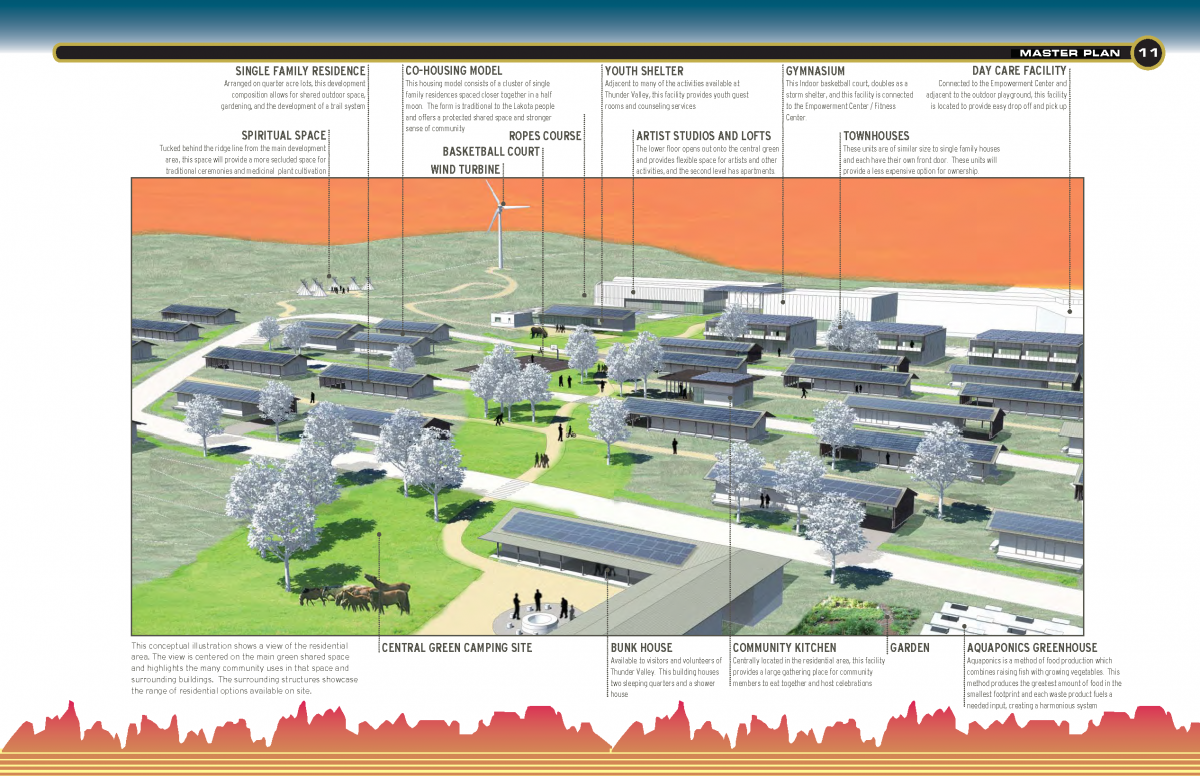

Thunder Valley Community Development Corporation, on the Pine Ridge Reservation, is developing a comprehensive community development initiative. This effort, which is being carried out in phases, provides a strong example of community planning and shows one way it can be done. Let’s take a look at the work of Thunder Valley.

On the following pages, we’ve provided a sample design showing what Thunder Valley is planning to include in their community development. Are there any elements in this design that you hadn’t thought of or that you’d like to include in your design?

Partner Check

Are there additional partners that you’d like to add to your initial list?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

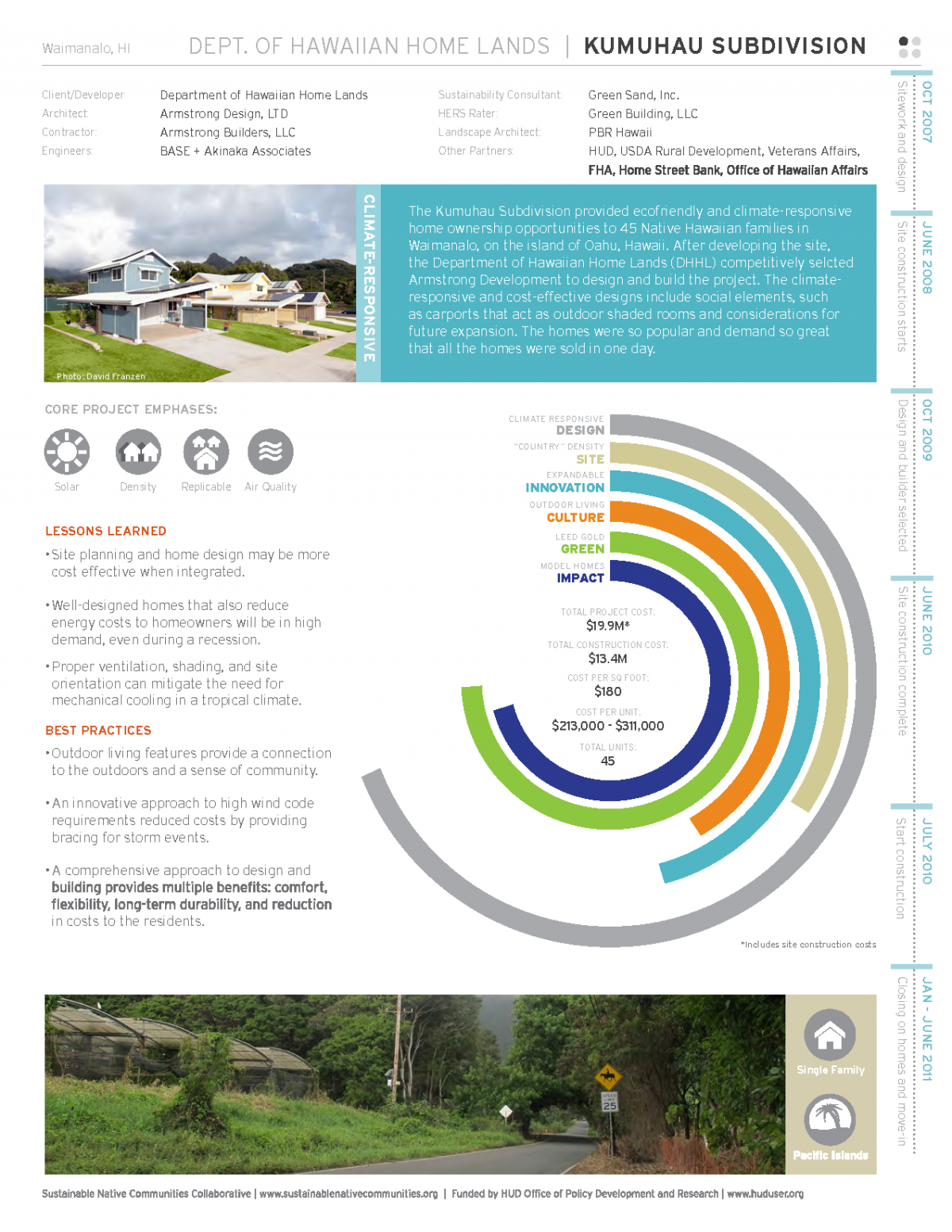

Community Design Case Studies

Developed by Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative

SNCC has also developed case studies highlighting sustainable tribal housing developments. From these case studies, best practices are identified, helping to clarify the innovative ways that tribal housing providers are overcoming challenges, including funding, infrastructure capacity, loss of cultural traditions, and economic development. Many featured teams approached housing development in a holistic manner, incorporating meaningful community engagement during the design process, reaching out to establish partnerships and collaborations that later proved critical for success, and solving complex challenges, from site planning to financing to tribal employment. Two case studies are below.